The EC Reign Month by Month 1950-1956

58: February/March 1955, Part II

|

| Crandall |

"Blackbeard" ★★★

Story Uncredited

Art by Reed Crandall

"U-Boat" ★★★ 1/2

Story by Carl Wessler

Art by Bernie Krigstein

"Mouse Trap" ★★

Story Uncredited

Art by George Evans

"Slave Ship" ★★

Story by Carl Wessler

Art by Graham Ingels

|

| "Blackbeard" |

|

| "U-Boat" |

Von Krohner: No, lieutenant, it is you who are the traitors! You Nazis . . . who betrayed a nation . . . a whole world . . . for the glory of a few greedy, brutal madmen!

Hass: Spoken like a true Prussian! You admiralty men thrive on war and when you think you may lose one, you look around for someone else to blame!

|

| "U-Boat" |

Martin Hawley only wanted to be a good sailor but the rest of the men on the Sea Spray would never let him forget how scrawny he was. Nor would they give him a break, stealing his food and making him take the top bunk (fer heaven's sake!), wearing the poor soul down. So, when Martin is caught stealing food from the store room and given six lashes with a cat-o-nine-tails, his patience runs out and he puts into play an elaborate plan to turn the men against the skipper and commit mutiny. The joke's on Martin, though, when the men murder the Captain and toss Hawley into a rowboat with no food or water to give the impression the Sea Spray had been scuttled. When he's found, nearly dead, by a passing ship, Hawley confesses his sins and tells the true story of the Sea Spray. The ship's doctor laments that Hawley never got a word out due to his lack of energy. "Mouse Trap" isn't a bad story but it's a bit on the ho-hum side; that might be down to the fact that the first two tales this issue are such firecrackers and "Mouse Trap" seems like such a familiar story. George Evans's art is just as tame as the script, with Martin Hawley resembling a skinny Quasimodo.

|

| "Mouse Trap" |

|

| "Slave Ship" |

|

| Graham may not be Ghastly anymore but he still has the Ghoods! ("Slave Ship") |

Jack: As I read "Blackbeard," I suspected that besting the title character in a sword fight might not be the smartest way to ensure long-term survival, and I was right. This is a great adventure tale with a satisfying conclusion and Reed Crandall's art is the best of what we see in the four stories in this issue. I was not that impressed by "U-Boat" and Krigstein's art did not work for me up until the end, when it kind of started to work. As I looked at the panel Peter selected above it finally hit me whose art Krigstein's reminds me of here (and sometimes elsewhere), with those heavy black lines: Frank Robbins! That's not a good thing. "Mouse Trap" is a pretty good story with an unexpected and effective twist, though it hardly showcases Evans's best work. Finally, "Slave Ship" is the second story this issue to feature an unexpected artist, though I think Ingels handles the task much better than Krigstein and this reminds me that the artist did some pulp work before he ever heard of EC.

MAD 21

"Poopeye!" ★★★★

Story by Harvey Kurtzman

Art by Will Elder

"Slow Motion!" ★★

Story by Harvey Kurtzman

Art by Jack Davis

"Comic Book Ads!" ★★★★+

Story by Harvey Kurtzman

Art by Will Elder

"Under the Waterfront!" ★★ 1/2

Story by Harvey Kurtzman

Art by Wally Wood

|

| "Poopeye!" |

|

| "Slow Motion!" |

Gosh, isn't it cool when you see a portion of a sports event shown in "Slow Motion!"? That golf swing, that boxing punch, that water-skiing moment--none is quite what it seems. Jack Davis works a little harder than usual on the art in this six-page series of vignettes, but by about page three all the humor has been drained out and it's just an endurance contest to get to the end.

Man, those "Comic Book Ads!" sure are stupid, aren't they? Learn how to use the power of hypnosis, sell greeting cards door to door, build muscle--we know them all. But wait! The amazing duo of Kurtzman and Elder turn the ads on their heads and give us five of the funniest pages I've seen yet in Mad. At first glance, these could almost be mistaken for the real ads, but (for once) reading the fine print is worth every moment it takes. Satirizing other companies' comic stars is one thing, but such a dead-on attack on the classic comic book ads took major guts. They really get the point here and tempt the young readers with promises of freebies. They also put a line for the name of your lawyer and spaces for your fingerprints. This is great, classic Mad!

|

| Genius! ("Comic Book Ads!") |

Things sure are tough "Under the Waterfront!" Terry just wants to get along with his girl and maybe do a little boxing, but labor troubles keep resulting in people getting killed. Terry nearly takes a dirt nap himself but manages to stay alive and keep working. This spoof of On the Waterfront doesn't worry too much about plot or even logic, but Wally Wood's art continues to amaze me. I always liked him, but reading our way through the EC line has made me love him and want to learn more about poor, doomed Wallace. This issue of Mad is really up and down--but that's kind of what Mad was all about, I guess--throwing lots of gags against the wall to see what stuck. On a side note, there are several pages of ads for the New Direction line and I must admit I'm not salivating at the prospect of a comic about psychoanalysis with art by Jack Kamen!--Jack

|

| "Under the Waterfront!" |

|

| For selling 1,000,000,000 packs . . . Jack Seabrook's unlisted number! ("Comic Book Ads!") |

|

| Kamen |

"Maniac at Large" ★★★

Story by Jack Oleck (?)

Art by George Evans

"Just Her Speed" ★★★

Story by Jack Oleck (?)

Art by Bernie Krigstein

"Where There's Smoke . . ." ★★★

Story by Carl Wessler

Art by Jack Kamen

"Good Boy" ★

Story by Carl Wessler

Art by Graham Ingels

Pretty young

|

| Eh, eh, ehh... ("Maniac at Large") |

Ed has finally managed to track down that no-good son-of-a-gun Marty Selzer to a roadside diner where Marty works as owner and server. Jubilant that his years-long search is finally over, Ed surprises his old chum with an order for some hot steaming lead served into Marty’s guts. But Marty being Marty, the soda jerk who stole Ed’s fiancé Shirley and a wad of dough (the money kind) tells the gunman that he’d be better off dead, explaining how miserable his life has been since that fateful day what with Shirley taking up with any man in town who will have her and spending Marty’s wages as soon as he earns them. But Marty isn't confessing all this just to cleanse his soul: he hopes he can stall Ed long enough for when the state trooper arrives at the diner for his nightly cup of coffee. Marty tries to appeal to random diners and travelers that briefly stop in, but they all exit quickly and leave the traitor to his fate. Finally the sound of the trooper’s motorbike fills Marty with victory and he gleefully tells Ed that everything he said was a lie and that Shirley is the best wife on Earth. Too bad for him that the trooper catches sight of a speeding car and hightails it out of the diner parking lot before he ever makes it inside. Ed takes this news in stride, killing Marty on the spot and leaving just as the trooper has caught up to the speedsters. Inside the car are Shirley and her latest boyfriend who kindly ask the policeman not to let Mr. Selzer know of their rendezvous.

|

| A typical Krigstein breakdown. ("Just Her Speed") |

Though the jury seems to be out regarding the penmanship of this story like “Maniac at Large” before it, “Just Her Speed” is a neat and efficient little killer with a nice double-socko ending that wouldn’t have been out of place at all on a program like Alfred Hitchcock Presents. Though the story does make us privy to Marty’s scheme to string Ed along so that the trooper can intervene, the reveal that Marty’s story has been one big hoax comes as a genuine surprise, and the grim dénouement that finds the weasel getting plugged over what was, as it turns out, the actual truth about trifling Shirley comes across as a nicely-delivered cosmic joke. Bernie Krigstein, up to his usual tricks with panel divisions, is seen in a more subdued form here.

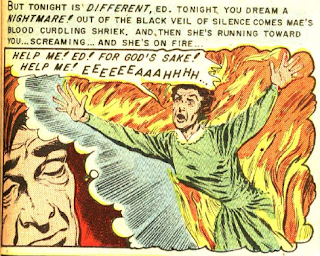

Ed has just about reached his last nerve in having to deal with his wife’s Mae constant nagging and complaining after he’s put in a hard day at the used bookstore he owns, and her incessant chatter about local gossip lulls him into an angered sleep. But Ed still has his dreams to himself, dreams like having pretty young Alma to himself, the winsome lady who works for Ed at the bookstore. Though Alma hasn’t made any forward advances or dropped any hints, Ed feels that all it would take to win her over is a dead wife and a heartfelt proposal, so armed with this bulletproof conviction he proceeds to hatch his own bonafide Spousal Murder Plot (patent pending from EC). Ed’s plan involves convincing the world (re: 1 other person) that Mae is a habitual smoker before dousing her with a can of benzene back at home and—presto!—accidental death by immolation, as far as the authorities are concerned. But before Ed can go through with his plan he’s introduced to Alma’s very young and handsome fiancé and given her notice all at once. Tail tucked between his legs over the foolishness of his enterprise, Ed later wakes up after his evening nap to find Mae flicking a lit cigarette at him after she’s doused him with the benzene.

|

| Do husbands dream of exploding shrews? ("Where There's Smoke...") |

Jim’s son Paul is a jerk. Everyone knows Paul is a jerk. Everyone but Jim, who doles out spankings and punishments but ultimately caves to his son’s sweet-talking ways. This develops over time into a mutually-harmful relationship wherein Jim is constantly suckered and Paul is constantly embroiled in affairs of increasingly criminal quality. When Jim is finally confronted with news of Paul’s nefariousness by no less than the police who tell the father about Paul’s shooting of a bootlegging kingpin, Jim turns and fills the closet where he has hid his son from the law full of lead. Jim then cries over his jerk son’s corpse.

Bust out the Kleenex, folks, cause we’ve got a weepie made to order here. “Good Boy” is about as hand-wringing as they come, a sorry swan song for Graham Ingels and this issue. Crime was never Ghastly’s forte, but like the story’s title suggests the artist was handed a real dog for his final assignment on this series. You can practically hear the organs piping by the time the last panel comes around.--Jose

|

| This would've never happened if he hadn't smoked those 5 marijuanas! ("Good Boy") |

Jack: I liked it much better than you did, Peter. "Just Her Speed" is my favorite, with its race against the clock story reminding me of a Cornell Woolrich setup. Krigstein's art is back to form and the twist ending was a complete surprise. Though "Maniac at Large" is overwritten and almost seems like an illustrated short story, Evans does a nice job with it and the ending was not completely predictable. I loved the guy banging on the window in anger because his book was going to be overdue! Ingels carries the day with "Good Boy," which is a rare Wessler script that doesn't begin at the end of the story and then unfold in flashback. The dad shooting the son behind the door reminded me of the Bugs Bunny cartoon, "Bugs and Thugs" from 1954, where Bugs throws a lighted match into a stove to prove that Rocky could not be hiding in there. I wonder if Wessler had the same thought? The timing is close. As for "Where There's Smoke . . .," the less said the better.

Panic #7

"Mel Padooka" ★★

Story by Jack Mendelsohn

Art by Bill Elder

"You Axed For It!" ★ 1/2

Story by Jack Mendelsohn

Art by Jack Davis

"Travel Posters" ★★

Story by Jack Mendelsohn

Art by Joe Orlando

"Them There Those" ★★ 1/2

Story by Jack Mendelsohn

Art by Wally Wood

Yeowch! Gulp! Ugh! Is it that time already for us to gulp down another tepid serving of Panic, the medicine that is the only officially sanctioned parody rag of MAD? Well yeah, I guess so!

|

| Child abuse: the stuff of comedy! ("Mel Padooka") |

“You Axed for It!”: No, we did not. Neither did Jack Davis, who is seen here wading his way through the sewage of yet another laborious TV show parody.

|

| You said it! ("Them There Those") |

“Them There Those”: Mendelsohn finally seems to get his sea legs and manages to deliver a fairly compact and outré parody of the SF classic Them! Most of the jokes land pretty well here, like the dazed little girl turning out to be a member of the EC Fan-Addict Club and a lush to boot. My favorite component of the story is secret FBI agent K-9, who has the uncanny ability to disguise himself as a globe, a hat rack, and finally a giant shoe, among other things. It’s such a bizarre non sequitur in what is for the most part a straight parody, and I only wish that Mendelsohn had followed his instinct to be weirder for the rest of the issue. It might not have meant that the material would have been funnier, but it sure would have been more memorable.--Jose

Peter: There's really no sense breaking down the contents of Panic #7, though I will say that, for a title that had become the nadir of the EC line, this issue sees an absolute scraping of the bottom of the barrel. There's an almost desperate plea from writer Jack Mendelsohn to like some of his stand-up material but, try as I might, I couldn't muster even a half-hearted smile. So, rather than waste any more space, I'll simply point to the header atop the Russ Cochran/Gemstone reprinting of Panic as the perfect summation of the title:

Jack: As a glutton for punishment, I read every last word and every single gag in this issue and did not get a single smile, much less a laugh. Jack Mendelsohn may have had a long and successful career, but I doubt he'd hold up this issue of Panic as one of his stellar achievements. What a waste of Elder and Wood's talents. Between Panic and Mad, EC really wore out the TV show parodies. I get that early '50s TV was bad, but they really harp on it and it's just not funny.

|

| Next Week . . . Will The Losers stay afloat? |