The DC Mystery Anthologies 1968-1976

by Peter Enfantino and

Jack Seabrook

Jack Seabrook

|

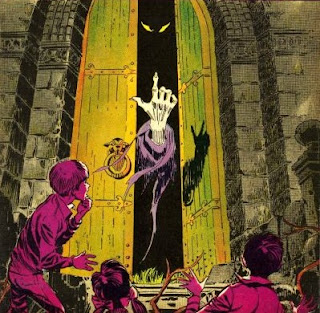

| Cover by Luis Dominguez, Alfredo Alcala, ER Cruz, Murphy Anderson & Joe Giella |

"The Man Who Died Twice"

Story by Jack Oleck

Art by Alfredo Alcala

"Master of the Unknown"

Story Uncredited

Art by Jack Kirby

(reprinted from House of Secrets #4, June 1957)

"Fireman, Burn My Child!"

Story by Michael Fleisher and Russell Carley

Art by Frank Thorne

"The Curse of the MacIntyres"

Story by Mary Skrenes

Art by Don Heck

(reprinted from The Sinister House of Secret Love #1, November 1971)

"See No Evil"

Story by Jack Oleck

Art by Alex Nino

"The Hairy Shadows"

Story by John Broome

Art by Murphy Anderson and Joe Giella

(reprinted from The Phantom Stranger #4, March 1953)

"Shadow Show"

Story by Mark Hanerfeld

Art by Jack Sparling

(reprinted from The Spectre #9, April 1969)

"This One'll Scare You to Death!"

Story by George Kashdan and David Kasakove

Art by E.R. Cruz

Peter: Cobbler Giles Mornay has never been happy with his lot in life; he's convinced he was born to be an aristocrat. He tries on the shoes of a nobleman and buys fancy clothes, but his wife mocks him and tells him to get back to his peasant's life. When Giles attempts to contact Satan through a black arts book he's attained, his wife hits the roof and burns the book. Tired of her constant berating, Giles murders the woman in a fit of anger. Up pops Satan, finally, to tell Giles he's done a great job and maybe they can come to an agreement. If Giles will hand over his soul, Satan will give him the life of an aristocrat he so desires. Giles agrees and Satan lays out the rules: Giles must cop to the murder and take his punishment. One year after his execution, his corpse will rise and Satan will find him a new body/home. Though wary of the bad rep Ol' Sparky has netted in the past, Giles agrees and, sure enough, one year later, his skeleton rises from the grave to seek out Satan. The devil, true to his word, transports Giles into his new body. Unfortunately, while Giles was moldering in his grave, France underwent a revolution and his new vessel is the Marquis de La Marre, an aristocrat about to be beheaded by the same peasants Mornay despised so much. Incredible Alcala art (in particular, Giles' rise from the grave) and a sly Oleck script combine to make "The Man Who Died Twice" one of 1974's high points so far. "Deal with the Devil" stories are a dime a dozen (or a quarter a dozen, thanks to 1974 funny book inflation) but Oleck manages to squeeze just one more surprise twist out of the formula. It's a reveal I never saw coming!

Jack: The extended opening sequence with the skeleton clad in decaying clothes is a tour de force by Alcala. It's a very intriguing set up that made me wonder if the payoff would live up to the opening. Surprisingly, it did, and the clue to the ending was fairly planted early on in the story when a date was provided. Unlike so many stories in Ghosts, where the date is just a historical footnote, it is a key element in this story, also one of my favorites so far for 1974.

|

| "Fireman..." |

businessman Bob Stadtler offers to buy a fire truck and charge a small fee for services. The town happily agrees but then, once Bob gets his truck, he has his hired goons starting fires all over town and he charges the victims exorbitant fees for putting the infernos out. When Bob shows up to a house fire and refuses to extinguish the flames because the owner doesn't have five grand, a little girl dies and the town turns violent. Bob murders his henchmen and then races out of town but doesn't get far when his car smashes into a hill. He's taken to a local hospital and stitched up and presented with the bill once he's recovered. When Bob tells the doctors he can't pay, they reclaim all their work. The next day, two surveyors stand on the hospital site (now an empty parcel of land) and wonder why the town intends to build a hospital way out in the middle of nowhere. They miss the skeleton behind the bushes. I have no idea what the climax of "Fireman, Burn My Child!" is supposed to mean. Are we to assume that ghosts (or demons or something) brought Bob to an imaginary hospital and then killed him when he didn't pay his bill? Then why does Bob's skeleton look as though it's been on that site quite a while? I can picture Michael Fleisher exclaiming "I've got it! He'll be a skeleton at the end! How cool is that?" but not thinking it through. I don't like Frank Thorne's art here, which is strange because I usually like Thorne's work. It almost looks unfinished, like that of another Frank (Robbins).

Jack: Stadtler is such a monster that I was reading this one right from the get go wondering what sort of horrible fate Fleisher had in store for him. What should have been the ending is pretty good, when the doctors tell him that they'll have to repossess his body parts because he can't pay, but the story goes on a page too long and the last page doesn't make much sense. I took it to be a scene from some future date, after his body had decomposed. The skeleton is in a wheelchair, so perhaps he didn't die after all.

|

| "See No Evil" |

Jack: I love Nino's artwork but even he can't save this bag of cliches and retreads.

|

| "This One..." |

Jack: Not a bad story--we've seen much worse. E.R. Cruz seems to get handed a lot of weak scripts and he always turns in artwork that is above average but not brilliant. I figured out what was going on right away.

Peter: "Reprints! We got reprints! Department." A decidedly mixed-bag of reprints this time out. A super-popular TV quiz show attracts the most intelligent contestants in the world. One of those, who calls himself "Master of the Unknown" and dresses head to toe in a Ku Klux Klan-esque robe, seems to know all the mysteries of the unexplained. He pinpoints the location of Excalibur and Atlantis, the whereabouts of the long-vanished mystery ship, the Carla Mona, and the latitude and longitude of the island home of the last-living Cyclops. The genius only slips up when he comes to the studio one day and forgets to cover his hands, which are lion's paws. The mystery man turns out to be... the Sphinx! That final panel, of the golden boy unmasked, is pretty doggone silly but the build-up is intriguing and suspenseful and Kirby's art is as dynamic as the stuff he'd pump out shortly thereafter for Atlas. In fact, this story could be mistaken for a "Tale to Astonish."

Jack: This story plays off of the quiz show fad of the time period and I really liked the twist ending, but I have a question for the Master of the Unknown: where did all my hair get to?

|

| "Master of the Unknown" |

Peter: I'm not sure how, but we managed to miss covering "The Curse of the MacIntyres" when it was first published in DC's The Sinister House of Secret Love #1 (which morphed into Secrets of Sinister House). I wouldn't have minded if we'd missed it again this time out. Romance, dwarves, romance, evil children, romance, family curses, romance, axe-wielding old ladies, and Don Heck. Do I need to say more? Well, how about that this funny book equivalent of a Barbara Michaels novel runs an insanely long 25 pages? That's three Johnny Peril adventures we could have read instead. What fan of House of Mystery in 1974 (or any other year, for that matter) read "MacIntyres" and thought "Hmmm, this is my cup of tea!" Not this twelve year-old, that's fer sure.

|

| Don Heck + Gothic Romance = Disaster |

Jack: We didn't start covering that comic till the name changed. As I read this story, memories flooded back of 1971 DC comics and lots of art by Don Heck. The Donster sure could draw cheesecake! The story goes on and on and follows the formula of a DC Gothic romance, but I was hoping the midget son of the romantic lead would turn out to be a killer leprechaun. No such luck.

|

| "The Hairy Shadows" |

|

| Jack Sparling.... Yecch |

Jack: I always thought the Spectre was a cool character and I liked the ending of the story, where the gigantic Spectre holds the bad guy in his great big, white-gloved hand, but I agree that the art is ugly. The Phantom Stranger story was fun and goofy. I love how PS turns up out of nowhere and says, "Sometimes I'm called the Phantom Stranger." Oh, OK. That explains it. And what are you called the rest of the time? A creepy weirdo who pokes his nose in other people's business? This was an uneven issue where the new stuff edged out the reprints in quality for a change.

|

| Luis Dominguez |

"Child's Play"

Story by Jack Oleck

Art by Ramona Fradon

"Corpus Delicti"

Story by Jack Oleck

Art by Gerry Talaoc

"Ms. Vampire Killer"

Story by Don Glut

Art by E. R. Cruz

Peter: Old Man Davis is having lots of trouble with those Shaw kids. They're obviously into voodoo and they view him as an old ruddy-duddy who needs a lesson learned. It's "Child's Play" for the demonic duo to terrorize Davis, making him believe sticking a pin in a doll will bring lots of pain and suffering. And then when little Ellen bakes a Mr. Davis gingerbread man and bites its head off... things get complicated. Here's a case of "He Said... They Said" with its dual viewpoint story line running side-by-side. Problem is, the uniqueness of the format wears out its welcome fairly quickly. The climax, with Old Man Davis writing down the details in his journal right up to the point where he gets his head bitten off (well, we assume that's what happens, at least) is straight out of H.P. Lovecraft. At least the old man didn't write "Aargh, my head seems to be separating from my body!!" When I see Ramona Fradon's highly stylized artwork, I can't help but think of Bruce Timm's similar work on Batman: The Animated Series.

Jack: When I read one of these comic book stories where one point of view runs down the left side and another runs down the right side I'm always a little confused about how I'm supposed to read them. Do I read left-right, left-right, etc., or do I read down the left and then down the right? It gets in the way of my enjoyment a little, but it did not mar this terrific story. I am enjoying every opportunity to re-encounter Ramona Fradon's art, which I don't think I fully appreciated 40 years ago. The conclusion is a winner!

|

| Bad horror stories can have the same effect on Jack |

Jack: It's hard to blame Arthur for killing Martha. She gets rid of the furniture he ordered, she throws out the chili he made for breakfast, she dumps his beer and--worst of all--she gives away his dog! Arf!

Peter: Present day Transylvania has the same problem with vampires it's had for centuries but the blood-suckers seem to be getting smarter and avoiding all the traps and pitfalls. Into this unnatural disaster area comes Professor Zarko, a decidedly atypical vampire hunter, geared up in low cut blouses and go-go boots and ready to kick vampire behind. "Ms. Vampire Hunter" puts a stake to the head monster and the villagers welcome peace at last. One man waits behind to put the moves on Zarko and discovers exactly how it was she was able to rid the world of the fanged demon: she's a vampire too and wants to eliminate the competition. Groan. If you've read as many of these snoozers as we have, you can guess the "surprise" the second the babe walks in the door. Don Glut is perhaps best known to horror comics fans as the creator of Gold Key's Doctor Spektor but, to me, he'll always be the guy who write the best non-fiction study of The Frankenstein Monster back in the early 1970s.

Jack: I'm a Don Glut fan from way back for his monster movie writing, but this story landed with a big thud. I did not see the ending coming but when it came I thought, oh no--not again!

|

| Nick Cardy |

"Color the Dead Black"

Story by George Kashdan

Art by Ruben Yandoc

". . . Better Off Dead!"

Story Uncredited

Art by Mike Sekowsky

"Kill the Demon Tiger!"

Story by Mike Fleisher

Art by Don Perlin

Jack: In the days of the Black Plague, London was devastated by disease but a small town outside the city has been spared until a family comes along seeking shelter. Soon, people begin dropping left and right and the villagers blame the old woman who came to town with the new family. Just as they are about to execute her for being a witch, along comes the son of the town's leader to tell them that, not only is the old woman not a witch, but her black cat is the only thing saving them from having to "Color the Dead Black." Rats bring the plague and cats kills rats. Though the villagers killed her cat just before the wise young man's return, they discover that it had kittens right before it died and so the village will likely be saved. Yandoc's art evokes the plague times nicely and the unexpectedly happy ending worked for me.

|

| "Color the Dead Black" |

Peter: Another history lesson disguised as entertainment. I'm not sure what's worse - a twist that falls flat on its face or the twist that never comes. With the latter, it always feels, to me, as though the story ends uncompleted. That's certainly true with "Color the Dead Black" (yet another really dumb title).

|

| ". . . Better off Dead!" |

Peter: Final panels like the one we get with "Better Off Dead" make me feel like I've missed something (like maybe a page or two?). If Borago is so frightening to Ellen, why is she smiling at us in that last panel? And raise your hand if you thought Jack was really Borago from the start? Yeah, big surprise that, right? If I didn't have the artist credit right here in front of me, I'd swear that Jerry Grandenetti teamed up with Don Heck on this one.

|

| "Kill the Demon Tiger" |

Peter: Just a paycheck this time around for Mike Fleisher (and probably a very small paycheck at that) and, with the quality that Mike pumps out for our entertainment, I think he's allowed that now and then. I was hoping the true identity of the tiger wasn't Sanisn but that trip to the dentist ("Oh my, what large teeth you have!") pretty much telecast it, didn't it? At one point, when the tiger grabs the little kid between its jaws, I thought the real Mike Fleisher might burst forth from this pablum and scream "I am Mike Fleisher and I'm going to show you something reeeeeally nasty!" but no, he's muffled by that happy ending.

|

| Luis Dominguez |

"To Sleep, Perchance to Die"

Story by Jack Oleck

Art by Abe Ocampo

"Till Death Do Us Part"

Story by Jack Oleck

Art by Luis Dominguez

"Time Plug"

Story by Steve Skeates

Art by Tony deZuniga

Peter: Unable to sleep due to continuing nightmares, Charles Sawyer slips further and further into madness. In his dreams, he sees a shadowy beast stalking him, getting closer with each encounter. Professional help is useless so Sawyer resigns himself to nights with little or no sleep. His wife continually pleads with him to return to his therapy but her concern comes off as nothing but nagging to the haggard Charles. His wife begs one time too many and Sawyer wrings her neck. When he looks up from her corpse, he sees the monster who has been invading his dreams but soon realizes he's looking into a mirror. Oh, I get it! We all have a beast inside of us that we keep at bay but is just that far away from emerging and doing nasty stuff. What a unique idea! "To Sleep..." is terminally dull. I thought for sure Sawyer's wife would rise from the dead after he'd strangled her and say "Doctor Evans--you must go see Doctor Evans just one more time!" She says that phrase so many times throughout the strip you'd think Bob Kanigher wrote the thing.

|

| "To Sleep..." |

Jack: Points to Jack Oleck for trying something a little different, but this psychological horror story falls flat. I figured out what was going on about halfway through, so the ending was no surprise. Ocampo's art is strong but can't overcome a weak story.

Peter: Jason Bowers wants to marry heiress Laura for her money rather than for love. She'll have nothing to do with him until Jason visits a local voodoo practitioner and buys a love potion. Bewitched Laura firmly in the bag, Jason gets his wife and his money, too. Laura plays the doting wife and does her knitting and reads about exotic hobbies while Jason spends all the money. Once the well is dry, the con man announces his intention of leaving Laura and heading for a warmer climate. Years later, after Laura is found dead of old age, it's discovered that one of her exotic hobbies came in handy. Jason is found in perfect condition, a book on taxidermy nearby. That clever climax would have seemed more of a surprise if a variation had not been plastered across the cover. Despite the E. Nelson Bridwell credit on the splash, this is a Jack Oleck script (the mistake is corrected in the letters page of WMT #15) and if I had been Jack, I'd have been pissed. There are a few plot holes I can't get past in this one. When Jason disappears, it's taken for granted he's gone despite the fact that Laura tells those who will listen that her beau is still in the house. Also, why make a big deal out of the voodoo queen and her joy juice when it's quickly dismissed and never addressed again? This is not one of Luis Dominguez's better jobs but the inker or maybe even the colorist might have had something to do with that. Many of his panels appear sketchy at best.

Jack: Now that Dominguez is replacing Nick Cardy as the main cover artist for the DC horror line, I was happy to see some of his work on the pages inside, yet the art in this story is not as good as what is on the cover. Had I not known the ending from the cover I might have enjoyed this story more.

Peter: On the run from the law, two bandits drive into a valley of magic, ruled by an old man with a secret. I can't say much more about "Time Plug" (a really dumb title, by the way), not because I don't want to give anything away but because I'm not sure I understand much of it. There's a time warp (sorta) and an old man who's lived for 200 years because of some crazy Indian magic (I guess) and... Well, that's it. There's some pretty pitchers to look at, though.

|

| "Time Plug" |

Jack: For the third time in this issue, the art is much better than the story. Doesn't that kind of sum up the DC horror line? You know a story is bad when Destiny has to come in in the last panel and explain what happened and what the title means. I think what he said is that, by killing the old man, a time plug was pulled and this allowed the last 200 years of progress to come flowing in. Steve Skeates is not impressing me.

|

| Nick Cardy |

"Flight of the Lost Phantom"

Story by Leo Dorfman

Art by Don Perlin

"The Corpse in the Cradle"

Story by Murray Boltinoff

Art by Alfredo Alcala

"The Specter of the Iron Duchess"

Story by Leo Dorfman

Art by Jerry Grandenetti

Jack: 1965, Hoboken, NJ--reporter Ralph Kelso visits the WWII aircraft carrier Washington, which is being taken apart. Touring the ship with its old caretaker, he hears and sees a ghostly plane trying to land and learns about the "Flight of the Lost Phantom." During the war, a pilot named Carter was the last to survive a bitter fight with Japanese planes, but when he tried to find his way back to the ship it was blacked out and the captain would not turn on the lights for fear that a submarine would find its target. Lt. Carter was doomed to fly his ghostly plane over the ship for eternity. The captain never recovered from having to make this tough decision, and he ended up as the ship's elderly caretaker.

|

| "Flight of the Lost Phantom" |

Peter: I thought the set-up for "Flight of the Lost Phantom" was intriguing and pretty darn creepy but it eventually devolved into just another Ghosts story.

Jack: On the cold and lonely border where Scotland meets England, hard working farmer Clyde Jameson spares no effort to get things ready for the baby his wife is carrying. Certain that it will be a boy and determined to give him a good start in life, Clyde leaves his pregnant wife to run the farm while he ventures off to make some cash by working on a fishing boat. He returns just in time to fetch the doctor to deliver the baby, and in the nights that follow he enjoys spending time with his wife and new baby. He fails to comprehend that the woman and child died in childbirth, so "The Corpse in the Cradle" and its mother are merely the ghosts of those he once loved. A lovely and elegiac story from Murray Boltinoff, of all people, with illustrations by Alcala that range from very good to masterful. We have watched his progress through the DC horror comics to the point where his human characters are extremely well drawn.

|

| A good example of Alcala's growing ability to draw a person who is not a corpse |

Jack: In Communist-era Czechoslovakia, Minister of Transport Jan Rasek takes matters into his own hands to stop another truck from being destroyed on the lonely mountain road that leads to an old stone castle. He does a little research and drives a truck himself, only to come face to face with "The Specter of the Iron Duchess," a ghost who is said to haunt the road as long as the castle stands. Jan convinces the National Council to let him blow up the castle and he drives a truck full of explosives up the road, but the Iron Duchess interferes and he ends up being blown up along with the truck and the castle. His plan worked, and the road is now safe. The first vehicle to pass when the smoke clears is the hearse carrying Jan's body. Danged if this isn't one of the better issues of Ghosts in some time! Grandenetti's art is no worse than Perlin's, but the stories are entertaining.

Peter: There might be the makings of a decent Ghosts story in there but it's buried beneath the tons of rubble known as Grandenetti. Chuckles rather than child are the order of the day. How pathetic a month is it when Ghosts is better than The Witching Hour?

|

| "The Specter of the Iron Duchess" |

|

| Nick Cardy |

"The Strange Shop on Demon Street"

Story by George Kashdan

Art by John Calnan

"The Baby Who Had But 'One Year to Die' . . ."

Story by D. W. Holtz (Dave Wood)

Art by Angel B. Luna

(reprinted from Unexpected 111, June 1969)

"The House That Death Built"

Story by Leo Dorfman

Art by Jerry Grandenetti

"The Half-Lucky Charm!"

Story Uncredited

Art by Gil Kane & Bernard Sachs

(reprinted from Sensation Mystery #115, June 1953)

|

| "The Strange Shop . . ." |

Peter: "The Strange Shop..." is the pits in both story and art and I have nothing else to say. Bailiff, take this story away, please.

Jack: Satanic schemer Orin Garth was master of "The House That Death Built." His false beacon on the seashore lured many ships to their doom and he profited by combing the wreckage for timbers he could use to build himself a home. He vows that one day his head will lie on a silken pillow. One night, as he is picking through the wreckage of another lost ship, he trips and his head lands on, of all things, a silken pillow. He nods off to sleep, unaware that he is lying in a coffin that washed up near the shore. When a wave takes the box out to sea and slams the lid, Orin is trapped forever but he got his wish. Whenever I find myself trying to be an apologist for Grandenetti, along comes a story like this to remind me why he was one of the worst artists at DC in the 1970s.

|

| How we feel sometimes . . . |

Peter: Grandenetti outdoes himself here. What in the world was the scale he was working in on that splash page? The cliff appears to be five times the size of the two figures below. That's either a very tiny cliff or those are very tall men. Which begs the question--how tall are the really big men floating in the sea?

|

| Oh! So that's it! |

Peter: The art in "The Baby . . . ," by Angel Luna, is about as primitive as art gets without resorting to stick figures. The climax made my head hurt really bad. Where do the New Year babies come from? The stork? Do they magically appear before each new Father Time to distribute? Even our '50s reprint, usually the best thing in these titles, blows big time. Aside from the outstanding Nick Cardy cover (which could be one of the ten best DC mystery covers of all time), the final issue of Secrets of Sinister House could be one of the worst issues of the year.

Jack: Amen to that!

|

| Did Mike Sekowsky walk by Gil Kane's desk and offer to help? |

|

| What the--? The mystery deepens in our next war-torn issue! On Sale Monday, April 6th! |