The Critical Guide to

the Warren Illustrated Magazines

1964-1983

by Uncle Jack

|

| Jack Davis |

Eerie #1 (September 1965)

(Ashcan Edition)

"Image of Bluebeard!"★★

Story by Bill Pearson

Art by Joe Orlando

"Death Plane" ★★1/2

Story by Larry Ivie

Art by George Evans

"The Invitation" ★1/2

Story by Larry Engleheart

Art by Manny Stallman

So, what exactly is an ashcan edition? Well, I'm glad you asked. Back in 1965, James Warren decided

Creepy was doing well enough to introduce a companion title. An ad was run in

Creepy #6 (

see way below) and

Eerie #1 was scheduled for a late 1965 release, but James Warren got word that an upstart company was about to release an

Eerie #1 as well. In order to convince his distributor (which was also the distributor for the new publisher) that Warren had claim to the title

Eerie, he had Archie Goodwin cobble together three stories that were scheduled to drop in the next couple of

Creepys and print 200 copies (in an odd digest size), to be dumped at the newsstand just outside the distributor's office (a better worded and more detailed synopsis can be found in

The Warren Companion).

|

| "Image of Bluebeard!" |

That rival publisher became Eerie Publications, which flooded the stands with titles such as

Tales from the Tomb,

Witches' Tales, and

Tales of Voodoo, filled with gorier versions of 1950s' pre-code horror comics (and, yes, I'd love to cover those one of these days before I die). The "ashcan" became a highly-prized and over-priced "collector's item" over the years (I've seen "legit" copies selling for over a grand) and pirated several times (if you look on eBay right now, there's one of those pirates selling a photocopy for about twenty a pop) but, luckily for all of us, the insides were reprinted very quickly (especially since the printing job was rushed and the reproduction was ugly!).

So, what did this "ashcan" serve up?

|

| "Death Plane" |

Mousy and homely Monica knows no man will come within spitting distance of her and time is growing short. She'll be an old maid before she knows it. Therefore, accepting a proposal from a man she doesn't love seems to be the smartest thing to do. That man happens to be Brian Cerulean, a brutish and elderly bearded gentleman who proposes to Monica and, after the wedding, brings her back to his isolated home in the forest. After only a few weeks, Monica begins complaining that she has nothing to do and too much time to do it. Brian promises she'll have company soon. Bored, Monica wanders into Brian's library and finds a book on Bluebeard. Reading a few chapters, the girl comes to the conclusion that her new husband is the one and only Bluebeard! When Brian begins spending a lot of time in his workshop, Monica spies him using a giant ax and naturally fears the worst. The next day, after a long drive into town, Brian comes back home and is greeted with a blade in the gut from his petrified wife. Calling the police, Monica confesses her fears but, once the workshop is opened, she discovers that Brian had been making cages for the forest animals he'd trapped to be her companions.

|

Stallman splash

Eerie #1 |

"Image of Bluebeard!" is nothing special, merely another variation on the "paranoid wife" hook. Orlando's art is muddy and amateurish. Interestingly enough, no effort is made to cover up the identity of Uncle Creepy in the pro- and epi-logues of "Image of Bluebeard!" but in the other stories, his profile is whited out. Also, I assume the production for the ashcan was based on photocopies rather than original art, as this story is very dark and "Death Plane" is very light.

During World War I, a "mystery ace" is shooting down planes from both sides, evading any attempts to shoot it down. In a rare moment of cooperation between the Allies and the Germans, both sides team up to exterminate the threat. One American pilot gets close enough to the enemy's cockpit before he's shot down in flames and discovers the eerie secret behind the "mystery ace."

As noted above, "Death Plane" has a very light printing tone and that doesn't help George Evans's delicate penciling one bit. If you take a look at the

Eerie #1 version and then the version printed in

Creepy #8, there's no comparison in quality. Evans's wonderful pencil strokes disappear in a shock of white. As far as the script goes, Larry Ivie generates healthy suspense before laying an egg with a head-scratching expository in the climax. An interesting concept but one not played out to a satisfactory conclusion.

|

Stallman splash

Creepy #8 |

Baron von Renfield's coach loses a wheel on his way home to his remote chateau and he comes face to face with a merry band of vampires. About to become dinner, von Renfield promises the blood-suckers he'll deliver four of his friends for their dining pleasure if they'll spare him. The vampires agree and the Baron heads back to his chateau, where he quickly sends out invitations to people who have wronged him in the past. Three entrees are served up to the vampires but von Renfield finds it hard to find a fourth. The vampires are not happy. A very confusing finale and a really dumb and predictable twist sink this one but I must say that Manny Stallman's pencils are a delight. His splash for "The Invitation" is exquisitely detailed (but most of that detail is, again, lost in the muddy photocopying) and his vampires very Bernie Krigstein-esque (a good thing). Stallman was a heavy-hitter in the Atlas horror title bullpen in the 1950s but only contributed to three stories for Warren.

-Peter

Jack: I enjoyed this short magazine! Too bad Monica never looked in a dictionary for the definition of her husband's surname. I actually thought the poor reproduction improved the look of Joe Orlando's art and I enjoyed the surprise ending to 'Image of Bluebeard!" If it's a story about WWI planes, call George Evans! "Death Plane" has an unfinished look and a weak ending. That full-page splash on "The Invitation" is impressive and I thought the art, and especially the layouts, were reminiscent of Alex Toth. Midway through the story, though, the words overwhelm the pictures and the conclusion was just silly.

|

| Frazetta |

Blazing Combat #2 (January 1966)

"Landscape!"★★1/2

Story by Archie Goodwin

Art by Joe Orlando

"Saratoga"★★★

Story by Archie Goodwin

Art by Reed Crandall

"MiG Alley"★★★

Story by Archie Goodwin

Art by Al McWilliams

"Face to Face!"★★

Story by Archie Goodwin

Art by Joe Orlando

"Kasserine Pass!"★★1/2

Story by Archie Goodwin

Art by Angelo Torres & Al Williamson

"Lone Hawk"★★★

Story by Archie Goodwin

Art by Alex Toth

"Holding Action"★★★

Story by Archie Goodwin

Art by John Severin

|

| "Landscape!" |

An old Vietnamese rice paddy farmer named Luong watches as guerrillas free his village and murder the former leaders. Luong's son is recruited as a guerrilla, but the old man just wants to be left alone to farm. American soldiers take the village from the Viet-Cong, then the North Vietnamese recapture it; each time, there is bloodshed and Luong doesn't see any improvement in his daily life. In the final attack, he is shot through the heart and his rice paddies are torched. The troops march off, unaware of the personal tragedy they leave behind.

Perhaps this anti-war tale was more effective when it hit the stands in late 1965, but today "Landscape!" seems trite and obvious. Joe Orlando does nothing special to elevate the narrative and Archie Goodwin's script tells a story that's been told many times before. War is futile and the little guy gets hurt. We get it. I suppose it was more surprising in the early days of the U.S. involvement in Vietnam, when anti-war sentiment was not yet widespread. Still, it's nothing we didn't see at EC during the Korean War.

|

| "Saratoga" |

It's October 1777, and the colonial forces under General Gates are bored and restless until battle erupts at "Saratoga." Gates has his men stuck in a position and they're getting hammered until a different general rides up and urges them on to attack the British. The frontal assault is a success and, ten days later, the British surrender. Who was the brash young general who changed the tide of battle? None other than Benedict Arnold, future traitor to the American cause!

It's not enough to have Reed Crandall's gorgeous, almost woodcut-like art to enjoy, but this story is a pip! I had no idea the young general was Benedict Arnold and now want to learn more about him and the Battle of Saratoga. This is what a good war comic story should do!

|

| "MiG Alley" |

"Pappy" Rice and his wingman had flown numerous missions in "MiG Alley" over Korea when Pappy was finally shot down, though he was able to eject safely before the plane hit the ground. Once he's back in the air on his next mission, Pappy is much more cautious than he used to be, and his wingman is worried. Pappy's landing gear is damaged from an enemy attack, and when he tries to land his jet too quickly it blows up and he is killed.

Al McWilliams does a terrific job with this fast-moving piece about jet fighting in Korea, and both story and art reminded me of classic DC War comic stories from the late '50s and early '60s, when MiG battles were a regular feature. I am really impressed by McWilliams's mastery of faces and planes and look forward to seeing more of his art.

The men who flocked to Cuba to fight in the Spanish-American War in 1898 did not have much experience in combat, and when Trooper Halpern is complimented for continuing up the hill after being shot in the arm, he thinks war is pretty cool. Sent back down the hill to deliver a message, he encounters a lone Spanish soldier, who tries to take his gun away. Vicious, hand to hand combat ensues and, after Halpern kills the enemy soldier with repeated blows to the head from a rock, he suddenly does not think war is quite so cool anymore.

|

| "Face to Face!" |

If I thought "Landscape!" was heavy-handed, the second story this issue by Goodwin and Orlando lands with an obvious thud. I don't understand why we have to put up with two stories by Joe Orlando when there were so many other great artists working for Warren. I also find it hard to work up much enthusiasm about the Spanish-American War.

|

| "Kasserine Pass!" |

A Sherman Tank operated by confident American soldiers rumbles across the North African desert, looking for any remnants of Rommel's Afrika Corps. At the "Kasserine Pass!" they are attacked by a German tank but return fire and make a direct hit--or so they think. Riding up to investigate, they come upon two German tanks in an ambush. The American tank is caught in a crossfire and everyone on board is killed.

The story's not bad and the art is above average, but I've seen better from both McWilliams and Torres. One thing is for sure: it beats the Haunted Tank!

Here's the WWI Flying Ace, "Lone Hawk" William A. "Billy" Bishop in his

Sopwith Camel Nieuport, zooming through the skies above France and Germany, shooting enemy planes out of the clouds while other pilots are dropping like flies. In the course of the war, he shoots down 72 planes and, to everyone's surprise, lives to tell the tale.

|

| "Lone Hawk" |

What starts out as a bit of a boring story about WWI fighter planes gradually sneaks up on you and delivers a surprisingly effective ending, in which the hero does not die on his last day out! Alex Toth's draftsmanship is excellent, but so many of the panels just feature planes in flight that he's not able to do as much as usual. Still, it's an unusual story and a pleasure to read.

The Korean War is nearly at an end, but new replacement soldiers arrive, including Stewart, who is scared and tries to run the first time he's fired upon. His tough sergeant insists that he grab his gun and start shooting enemy soldiers, but Stewart gets a little too wrapped up in his job. When a cease fire is declared, he is at loose ends and has to be dragged away from the battlefield.

"Holding Action" ends this issue on a strong note, as Goodwin's script is brought vividly to life by the great John Severin, an artist I've grown to appreciate more and more as we've worked our way through these blogs. Some of his individual tricks are on display here, including the wordless panel with one character glaring at another, and the multi-panel sequence where only small details change but have a big effect. He was an extraordinary comic artist and he seems to have excelled at war stories.

-Jack

|

Severin's wordless glare

("Holding Action") |

Peter: I've never read any of the

Blazing Combat stories prior to working on this blog and if I hadn't just absorbed all of Harvey Kurtzman's EC war stories recently, I might have thought some of these were pretty powerful. "MiG Alley" and "Landscape" certainly have their powerful moments but, overall, I have to say I'm disappointed in the title so far. Yep, most of the art is top-notch, but a lot of the scripting is obvious and Goodwin seems to be going for the easy moral. "Holding Action," in particular, seems cliched and predictable. But that may be due to my Kurtzman overload. Archie was influenced by Harvey's writing, that's clear to see, but most of his scripts are reading like homage rather than building on any inspiration. "Landscape" is the infamous anti-war story that pretty much killed

Blazing Combat, as detailed in an interview with Archie Goodwin's widow, Anne T. Murphy (who would also contribute to Warren Publishing), in

The Warren Companion. Milton Caniff, creator of the "Steve Canyon" comic strip, writes in to praise issue #1. Archie blushes with pride but the gremlins misspell Caniff's first name!

|

| Frazetta |

Creepy #7 (February 1966)

"The Duel of the Monsters!"★★

Story by Archie Goodwin

Art by Angelo Torres

"Image of Bluebeard!"

(see Eerie #1 above)

"Rude Awakening!"★★1/2

Story by Archie Goodwin

Art by Alex Toth

"Drink Deep!"★★

Story by Otto Binder

Art by John Severin

"The Body-Snatcher!"★★★1/2

Story by Robert Louis Stevenson

Adapted by Archie Goodwin

Art by Reed Crandall

"Blood of Krylon!"★★1/2

Story by Archie Goodwin

Art by Gray Morrow

"Hot Spell!"★★★★

Story by Archie Goodwin

Art by Reed Crandall

|

| "The Duel of the Monsters!" |

Murder! In a small village in Spain in the Year of Our Lord 1811, Sgt. Vega's reaction to the bloody murder of one of the town's residents is unexpected--he is frustrated that the violent deed will have an adverse effect on his way of life! Vega realizes right away that this is the work of a werewolf, and he discovers that the hairy beast also found Vega's sleeping coffin and ruined it by placing a cross inside. Vega, you see, is a vampire, and he does not like the idea of another monster eating up the tasty local populace. The sergeant suspects Alphonso, the night watchman at the cemetery, of being the werewolf, and goes to his home one night to confront him. The werewolf attacks and "The Duel of the Monsters!" ensues but, once both vampire and werewolf have inflicted fatal wounds on each other, the werewolf turns out to be Vega's colleague, Corporal Ruiz, and Alphonso turns out to be a ghoul who set up the battle in order to feed his own unholy appetite.

|

| "Rude Awakening!" |

Whew! That's a lot of plot for such a lousy story. The "old Spain" setting never interests me much and the final showdown is a real letdown. Having the night watchman turn out to be a ghoul is the corny icing on the cake. The Torres art is okay but can't hold a candle to Frazetta's cover, which purports to illustrate a scene from this story.

"Image of Bluebeard!" follows, with much better reproduction quality than we saw in

Eerie #1. The art by Orlando isn't half bad, for Orlando, but I kind of liked the xerox-quality heavy blacks in the

Eerie version.

Mr. Asher has a recurring nightmare in which he is held down by hooded figures while a man in glasses plunges a knife into his chest. He wakes up in the morning from the dream, has it again on the subway on his way to work, and still again in the elevator at work. Lying down at the office, he has the nightmare again, but this time he wakes up and falls backwards out of a third-story window. He is rushed by ambulance to the hospital and the last thing he sees in the operating room is the man with glasses approaching him with a scalpel.

|

| "Drink Deep!" |

"Rude Awakening!" reminds me of a DC horror comic story in that the writing is lamebrained but the art (and layout) is excellent. I wonder if Archie Goodwin was recalling the "Perchance to Dream" episode of

The Twilight Zone from back in 1959. Toth's work continues to impress me.

Reggie Beardsley may be rich and have his own yacht,

The Golden Galleon, but he treats its crew terribly. The Beardsley family fortune can be traced back to pirate Black Beardsley who, two centuries before, scuttled ships across the Caribbean in order to build up his own pile of gold. Reggie's crew quits in disgust, so he hires new men and sails off to the spot where his ancestor had scuttled his last ship. Late one night, his crew deteriorates into rotting corpses or skeletons that drag him onto the wreck of the old ship that had risen up for the occasion; once Reggie is aboard, it sinks again and he dies, after having to "Drink Deep!" of the briny water.

Not one of Severin's best efforts, but passably good, this waterlogged tale is dragged toward the bottom of the

Creepy ocean by a predictable plot.

|

| "The Body-Snatcher!" |

Dr. MacFarlane, professor of anatomy at the Edinburgh Medical School, depends on the services of "The Body-Snatcher!" named Gray, who provides fresh corpses for the students to dissect. His new assistant, Fettes, is aghast when Gray brings in the body of a young flower girl, since Fettes realizes she must have been murdered rather than taken from her grave. MacFarlane is content to look the other way until Gray becomes too much trouble; at that point, MacFarlane kills Gray and the former body snatcher becomes the latest body to be cut up. One rainy night, Gray and Fettes head off to the graveyard and dig up the corpse of a young woman. They transport the body back in the front seat of the carriage between them, but when the horse bolts, a flash of lightning appears to reveal that the corpse is actually that of Gray!

|

| "Blood of Krylon!" |

The end doesn't seem to make sense, so I looked up the plot of the short story on Wikipedia and it seems to be the same as that of the comic adaptation. I vaguely recall the wonderful film with Karloff and Lugosi and the classic horror scene in the coach, but for some reason I thought it was a guilty imagination at work. Whatever the point of it all, Crandall's art is again superb and the mid-nineteenth century London setting really fits his style.

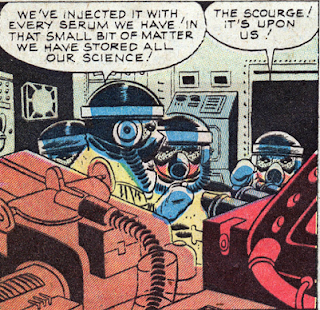

Frustrated by the poor prospects on Earth, a vampire named Remick rides a spaceship to a planet named Krylon, where he hopes to feast on the inhabitants. Arriving and anxious to taste the "Blood of Krylon!," Remick flies toward a city and sees a yummy fellow below. Just as he's about to start dining, the sun comes up and fries him; it seems night are shorter on this planet and poor Remick did not account for that.

Sometimes the dumbest stories are the most fun! Gray Morrow's art looks like he used some kind of wash or water color technique, if not paint, and it's really cool. The concept reminds me of the Atlas comic series from the '70s,

Planet of the Vampires, though that was kind of the opposite situation.

Tied to the stake and burned as a warlock in 17th-century New England, Rapher Grundy curses the people of Warrenville and their descendants. Three hundred years later, a series of folks have died in accidental burnings and suspicion falls on an artist, new to the village and a dead-ringer for Frank Frazetta. The dimwitted townsfolk burn down his house with his young wife inside, then beat him to death. Just then, the spirit of Rapher Grundy rises and drags the four evil townsfolk down to Hell!

As

Creepy develops issue by issue, we're seeing flashes of brilliance along with selective instances of increased gore and violence. "Hot Spell!" is outstanding in story and art, but it makes me wonder why editor Goodwin saved the best story in the magazine for the last position? Why not lead off with this?

-Jack

Peter: The two high points here are "Hot Spell!" and "The Body-Snatcher!" Archie's adaptation is the best one thus far (and I'm

not the biggest fan of these "Creepy Classics") and Crandall's art on both stories is as great as it was in the EC days, with that "Hot Spell!" splash a stunner. "The Duel of the Monsters!" is a silly monster mash-up that contains not one iota of the excitement promised by Frazetta's cover. Overall, it's still the art that makes us turn those pages as most of the the scripts seem like warmed-over EC but, ohhhhh, that art!

|

Next Week...

Jack and Peter decide that, yes,

they'll see this through to December 1976 |