The DC Mystery Anthologies 1968-1976

by Peter Enfantino and

Jack Seabrook

|

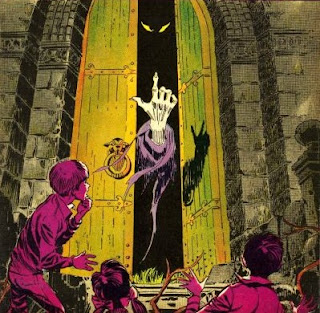

| Redondo studio? |

The House of Mystery 227

"The Vengeance of Voodoo Annie"

Story by Russell Carley and Michael Fleisher

Art by Nestor Redondo

"The Haunting Wind!"

Story by Jack Miller

Art by John Giunta

(reprinted from

The Phantom Stranger #2, November 1952)

"Cry, Clown, Cry"

Script Uncredited

Art by Bill Ely

(reprinted from

House of Secrets #51, December 1961)

"The Town That Lost Its Face"

Story Uncredited

Art by Bill Ely

(reprinted from

House of Secrets #50, November 1961)

"The Weird World of Anton Borka"

Story Uncredited

Art by Howard Purcell

(reprinted from

House of Secrets #37, October 1960)

"Demons Are Made... Not Born"

Story by Don Glut

Art by Quico Redondo

"The Girl in the Glass Sphere"

Story Uncredited

Art by Joe Maneely

(reprinted from

House of Mystery #72, March 1958)

"The Carriage Man"

Story by Russell Carley and Michael Fleisher

Art by Alfredo Alcala

Peter: Henry and George, the successful owners of Jarrett Bros. Toy Co., have one thing in common: they're both in love with George's wife, Connie. That's bad news for both of them since Connie is playing Henry against George to obtain a share of the toy company. The sultry vixen wants Henry to murder his brother and then run away with her so Henry hooks up with an old hag known as Voodoo Annie, who guarantees her black magic will dispose of George lickety-split. She gives Henry a voodoo doll and tells him to stick a pin in it after midnight but when Connie sees the doll, she throws it out her penthouse window in anger. A few hours later, George is found dead, an apparent suicide. It's not long before the cops come calling, citing a letter written by George shortly before his death, wherein he foretells his own death at the hands of his wife. The police haul Connie away, leaving Henry smiling, happy that his fake letter scheme worked. He'll now inherit the other half of the toy biz and he'll be a gazillionaire. Voodoo Annie calls, wanting fifty grand to keep her trap shut, but Henry's having none of that. He meets with Annie on a cliff and, as he's about to shoot the old woman, she produces a Henry doll. As he blasts her, she drops it over the cliff and Henry tumbles to his death attempting to retrieve it. Some time later, their bodies are found and the cops allow how it's great they finally got con-woman Voodoo Annie, who would mold dolls, murder the subjects, and then blackmail her mark. There are bits of Fleisher peeking through in "The Vengeance of Voodoo Annie" but not much and the whole thing tastes a little rancid, like three day old leftovers. That Scooby-Doo expository at the finale doesn't help things at all. I will admit to not seeing the second twist (Henry's con on Connie) coming and Nestor's art is customarily good so it's not all bad.

Jack: Definitely second-tier Fleisher, and Redondo's art isn't as strong as we've grown used to, either. The best thing about this story is the length--at 12 pages, it's longer than the typical DC horror tale and thus has a little more plot.

Peter: Rare book collectors Solyomi and Kruzz have been looking for the legendary "Chronicles of Satan" tome for decades and, at long last, it has fallen into Solyomi's hands. The book is supposed to contain spells and incantations that can raise demons for fun and profit. Kruzz decides he wants the book to himself so he offs his partner and heads back home with the treasure. There, he draws his pentagram and recites the mumbo jumbo but the result is not what he'd thought it would be: he himself becomes a demon. Satan arrives to inform Kruzz that "Demons are Made... Not Born!" and that the "Chronicles" were put on earth to lure greedy saps into his control. Pretty good story with knockout graphics, "Demons..." also has a true twist in its tail, one that I didn't see coming. I would question Solyomi's assertion that, based on a quick scan of the contents, the "Chronicles" is indeed authentic and written by Ol' Sparky himself! Basing that on what? Handwriting samples? Common themes found in the author's other work? I may have mentioned this before but writer Don Glut has produced a body of fun genre work, from his horror stories such as this to the adventures of his supernatural comic character, Doctor Spektor (published by Gold Key Comics), to two of the most essential genre reference books ever written,

The Frankenstein Legend and

The Dracula Book.

Jack: Quico Redondo outdoes his brother Nestor this time around with some atmospheric art, marred only by an unintentionally funny panel that shows the newly made demon running from the cops.

Peter: A series of gruesome murders have the police baffled until an abandoned buggy leads them to Henry Plimpton, "The Carriage Man." With the unwitting help of Henry's lady friend, Elaine Ratner, the detectives set a trap designed to bring Henry's nasty habit out into the open. The scheme works and Henry's alter-ego, that of a werewolf, is unmasked. That's it. No twists, turns, or surprises and twenty pages that are padded with lots of smelly stuffing. Like "Voodoo Annie," there's not much of the Michael Fleisher we know and love here. I kept waiting for something unique to pop out at me but the thing just kind of lays there and unravels. Alcala, however, is aces. From the intricate detail of his city street scenes to that full-pager of Henry attacking his customers in the park, there was nobody illustrating horror comics quite like AA (and, I hate to sound the alarm, but we only have a handful of Alfredo left to sup on as he'll soon be commuting between other DC titles and work at Marvel). It's nice to know Henry was able to keep at least a bit of his human sensibilities about him and didn't kill his horse (who must be pretty used to the transformation by now since he didn't even buck). A looooong, dreary slag.

Jack: I thought this was very Fleisheresque, especially the graphic murders of Phil and Joclyn in the park and the concluding graphic death of the werewolf. Also very in line with the Fleisher I remember is the line of cruelty that runs through the story. The story of Henry and Elaine recalls the plot of Chaplin's

City Lights, where the tramp is loved by the blind girl who can't see his clothes but understands his inner goodness. Here, Henry is a kind man who turns into a murderous fiend at the full moon. The strange part of this story is that the police are so callous and cruel. They make fun of Henry and Elaine and show no compassion whatsoever when they kill him in his werewolf form. The story troubled me from that aspect. Shouldn't they have done more? I guess they had to kill the beast, but they at least could have given some explanation to poor Elaine.

Two things struck me as funny in this one. First was the murder of Phil, whose girlfriend Joclyn insists that he get her out of there while he's busy getting his throat ripped out. Second was this exchange between the cops:

Cop #1: "His throat's ripped out . . ."

Cop #2: "Yeah, well you win some, you lose some!"

It's stories like this that made Fleisher a polarizing figure.

Peter: Usually, I attach words such as "innocent," charming," or "imaginative" to the reprints in these 100-pagers but, this time out, the adjectives that jump out at me are "tedious" and "inane." From the silly "Haunting Wind" that follows a temple defiler to the clown who's never satisfied with the amount of laughter he garners to the goofball invisible aliens who make Anton Borka's dreams come true, there's just a bit too much hokum going on. The only rerun worth its paper is Joe Maneely's "The Girl in the Glass Sphere," wherein a reporter stumbles on the story of a lifetime when he discovers that a millionaire's girlfriend is a real-life siren (luring the sailors to the rocks and all). Stan Lee once said that if Maneely, who made his name on Atlas's eyeball-pleasing (and sadly short-lived)

Black Knight (1955-56), had not been tragically killed at a young age, he would have become another Jack Kirby. Imagine a world where Joe Maneely illustrated Doctor Strange and The Mighty Thor.

Jack: One of the most ridiculous reprint stories this time out is "The Town That Lost Its Face," in which a man discovers that a mysterious power has been transferred to him from an old Indian face carved in the side of a mountain. The power causes everyone who looks at him to lose their facial features. The weird part of the story is that he has his own helicopter, which he flies over to the side of the mountain and climbs out of down a rope ladder, leaving the helicopter hovering there in mid-air without a pilot. He fixes the problem at the end by carving a new face into the side of the mountain with a jackhammer in record time. How is the jackhammer powered? By a cable that goes up to his helicopter, still hovering faithfully in mid-air.

|

| Luis Dominguez |

The House of Secrets 125

"Catch as Cats Can!"

Story by E. Nelson Bridwell

Art by Luis Dominguez

"Pay the Piper"

Story by Jack Oleck

Art by Alfredo Alcala

"Instant Re-Kill!"

Story by Steve Skeates

Art by Frank Robbins

Peter: Baron Von Schlamm rules over a small medieval European village with an iron glove, bleeding its peasants dry with his taxes and petty laws. One of those petty laws makes the owning of a cat illegal. That doesn't sit well with a little blonde girl and her feline, Zauberkatze. In fact, whenever one of the Baron's men comes near the kitty, bad accidents happen. Hearing of these mishaps, the Baron himself decides to put a stop to this little girl and her "pranks." But when Von Schlamm confronts the cat, it screeches "some strange sounds" and the Baron disappears. Thankfully, Abel arrives to let us know that the cat is a witch or else we'd have never known. "Catch as Cats Can" is a charming enough fable, with nice art by Dominguez, but since Bridwell saw fit to translate the meaning of the cat's name, couldn't he have let us know the meaning of the magic words it screeched as well?

|

| Easy for you to say! |

Jack: I know very little German, but I know that "Zauberkatze" means "magic cat," which pretty much told me all I needed to know on the first page of this story. Still, the Domiguez art is impressive and Bridwell at least manages to tell a story with a beginning, a middle, and an end, which puts this a notch above what we get this month in

Ghosts.

|

| Exquisite detail by AA |

Peter: A particularly nasty man, Michael Duncan forces his handicapped son to mountain climb with him and, after a very acidic rant directed at young Andy, is surprised when a man dressed in a piper's suit arrives to scold him. Despite the anger he feels, Michael hires the man to guide them down the mountain. While his father sleeps one night, Andy goes off with the piper to a "fantasy land" where his infirmities are magically healed and children flock to him to play. When the youngster tells his father of the magical place, Michael flies into a jealous rage and sends the piper off. That night, the man returns to rescue Andy again, this time for good. Michael sees the piper and his son open a door in the mountainside and disappear. When he goes down to the village for help, the police scoff until he describes the guide and the burgomaster shows him an ancient book containing a drawing of the piper. He is death. Despite the over-the-top portrayal of the sadistic Michael Duncan (yep, I know there are really nasty fathers out there but there's an almost humorous piling on of hatred toward Andy that just doesn't work), this has one of those really nasty kicks in the rear that the DC mystery writers can cook up now and then (usually directed towards feeble children, I hasten to add) and Alcala's exquisite art elevates "Pay the Piper" into one of the year's best. It's bizarre that we feel relieved that the child is dead and free of his brutish father when there must be some other way to save him. This is one that gets better the more you think about it.

|

| More Alcala... just because we can. |

Jack: I wonder if Jack Oleck submitted this as part of a two-for-one deal with last issue's "Make Believe," which is such a similar story. In both, a disabled child is taken away by an adult man to a fantasy world where he can be happy and free of disability. For some reason, it works better this time around, mainly due to Alcala's gorgeous art. This will be in the running for the year's ten best, at least on my list.

Peter: Has-been actor Ned Randolph just can't seem to get a good take of the scene he's shooting with the groovy Laura. The director hates the first take of Ned gunning down Laura in a jealous rage so he has him slap her around a bit first. Still not good enough, the director has Ned switch to a shotgun. Much better. Unfortunately, that's when the cops break down the door and we find out the movie is all in Ned's head and Laura's been blasted to bits. "Instant Re-Kill" has a decent twist ending but I defy you to get past annoyance and into enjoyment when you gaze at Frank Robbins' Rorschachs. Check out Laura's relaxed pose in that first panel (

below); can the human body actually bend like that?

Jack: Another weak script by Steve Skeates, perfectly matched by horrible art by Frank Robbins. The actress's pose in the first panel is an example of Robbins's tendency to ignore the reasonable possibilities of what the human body can comfortably do. Suffice it to say, the ending makes no sense, but did we expect any more?

|

| Nick Cardy |

The Witching Hour 48

"There's a Skeleton in My Closet!"

Story by Carl Wessler

Art by Ruben Yandoc

"Tragedy in Lab 13!"

Story and Art Uncredited

"Curse of the Chinese Charm"

Story by Carl Wessler

Art by Frank Carrillo

Jack: Grant Morrow was a millionaire who had a son named Lance and an adopted son named Wade. He doted on Lance, who was a ne'er do well hippie, while straight-laced Wade felt unloved. When Grant dies and Lance comes home for the reading of the will, Wade rigs the brakes on Lance's car and so causes his death. Wade then learns, to his horror, that "There's a Skeleton in My Closet!" Detective Lonergan suspects Wade of causing Lance's death, but Wade is so frightened by what appears to be the skeleton of his dead brother that he falls off a balcony to his death. Lance's hippie wife, Aimee, shows up to collect the inheritance, and we suspect that she had something to do with the fright campaign that led to Wade's demise. Not a bad little story, though nothing original. Rubeny's artwork holds the pieces together.

Peter: Bloodthirsty relatives? Check. Big inheritance? Check. Phony ghost? Check. Expository for those of us too dumb to see the obvious? Check. Typically good art by Yandoc? Check.

|

But he's not through with his

gig as one of the Village People! |

Jack: Dr. Chang invents a miracle drug that prolongs life. A pharmaceutical company offers its sales rep $1,000,000 to get the secret formula, so he woos and proposes marriage to Chang's lovely assistant. They hatch a plan to poison themselves and Chang so that he will tell them the formula and save all of their lives. But a "Tragedy in Lab 13!" occurs when they get their hands on his notebook and find that all of the writing is in Chinese! I let out a big laugh when I read the end of this one. I did not see that coming. Bravo to the unknown writer who thought this up. The art's not bad, either!

Peter: Oh, poor Jack needs a vacation again. Tell me why these two dopes would drink the poison? There's no logical reason for it. All they'd have to do is lie to Chang and tell them they were feeling the effects as well.

|

| Woe is Woo?!? |

Jack: Shanghai, 1947, and Hester Drummond buys a charm in a Chinese curio shop. The salesman tells her that the charm will bring good fortune to the ambitious, so she gives it to her boyfriend, Kevin Ames, and sends him on an undersea treasure hunt. He comes up with valuable loot but barely escapes a man-eating shark. Each time he goes back down for more treasure, the charm weighs heavier on him, until he finally takes it off and becomes shark food. Hester doesn't miss a beat and sends another boyfriend, Paul Wethersford, down to get the charm. The "Curse of the Chinese Charm" ensures that he'll meet the same fate as Kevin, but what does Hester care? It was her ambition that was rewarded. "Chinese Charm" is by the numbers, with no surprises.

Peter: Can you duck a shark underwater? Seems a very hard task to me. This one is utterly drab. The climax reads as though Wessler was under the impression he had a few more pages to wrap up his story and, at the last minute, Murray called down to the lunchroom and told Carl he'd have to cut it short.

|

| Kevin decomposed very quickly |

|

| Luis Dominguez |

Weird Mystery Tales 14

"Blind Child's Bluff!"

Story by Steve Skeates

Art by Ruben Yandoc

"The Price"

Adaptation by E. Nelson Bridwell

Story ("The Price of the Head")

by John Russell

Art by Alfredo Alcala

"Flight Into Fright"

Story by George Kashdan

Art by Ernie Chan

Peter: Bucky is accused of murdering little Cathy’s parents but Cathy knows her dog had nothing to do with the killings, even if she

is blind. No, Cathy is convinced her dead father’s ghost took care of her conniving stepmother and Mr. Jones. When the police arrive to shoot the dog, daddy’s ghost makes an appearance and the cops hightail it. Cathy and Bucky are left all alone in the big house. Well, alone except for daddy. Here’s another really dumb story that was obviously accepted because there would otherwise have been five white pages. I’d opt for the blanks after reading “Blind Child’s Bluff.” So, the bloodthirsty police (“Come on! Shoot! Right between the eyes!”) are convinced there’s a ghost after all and run out the door, leaving little blind Cathy to fend for herself? In what universe?

Jack: That was quick! Another poor story by Steve Skeates. I'm also getting a little tired of Ruben Yandoc's art. Give me more Gerry Talaoc!

Peter: Pellett is a disgrace, spending most of his days on the Polynesian island of Fufuti in a drunken stupor. The only one who still has faith in Pellett is his man-servant, Karaki, who dutifully hoists him upon his shoulder and takes him home to clean him up after Pellett has closed down every bar on the island. This morning, however, Karaki takes Pellett down to the beach, steals a rifle and a catamaran, and hobbles all the village boats so they can’t follow. They head out to sea where the drunken Pellett finally wakes up with the DTs and queries Karaki as to their destination. Balbi, Karaki’s birth place is the answer. After a month at sea, the duo arrive in Balbi, where a suddenly sober Pellett thanks Karaki for all he’s done for him. Is there anything Pellett can do in kind? In Balbi, a white man’s head is “desired above wealth and fame” and Karaki claims his prize. Based on the short story, “The Price of the Head,” by John Russell, “The Price” is a shot of class in an issue that needs it badly. I had heard this story dramatized on the old time radio show

Escape years ago (and you can listen to that show

here) so was familiar with the plot but E. Nelson Bridwell does a great job of condensing and editing out the dry bits and leaving a cohesive, enjoyable narrative. Pellett resigns himself to the fact that he’ll be beheaded but tells Karaki he owes his friend that much and more for all he’s done for him over the years. Alfredo always soars when given a story set in a tropical clime and he doesn't disappoint here.

Jack: "The Price of the Head" by John Russell was first published in the May 20, 1916 issue of

Collier's and may be read

here. I wish Joe Orlando had done more of these adaptations of classic stories, since they are so much better than most of the new stories written by the DC horror scribes. The art by Alcala is flawless, of course, and Bridwell's script follows the story closely. The story ends with Pellett telling Karaki to shoot; the comic version adds two panels to depict the aftermath, which works well in the graphic story format.

|

| The grim climax of "The Price" |

Peter: With the help of hunchback Quasimodo, Count Dracula has opened a travel agency that specializes in showing tourists the vampire country of Transylvania. He signs up three cool, hip cats and accompanies them to his castle, where he shows them the coffins of the vampires. The hippies scoff and this outrages the vampire, who locks them in with the awakening vampires. The flower children manage to escape (faulty locks?) but are attacked by vampire bats outside the castle and bitten. The next day, they are on a plane back to America as children of the night and Dracula smiles as he surveys his new “disciples.” If this was meant to be parody, I’m not laughing. Utterly juvenile, “Flight Into Fright” scrapes the bottom of a seemingly bottomless Kashdan barrel. Why is Dracula free to wander around during the day? Uh, George, some rules might be helpful. And how the hell did the three nitwits get out of that locked dungeon? We see Drac slam the door and a couple pages later they’re free. Uh, George, a little continuity might be helpful. The usually reliable Ernie (Chua) Chan turns in a job that could be conservatively labeled "cartoony." The whole package would have been more comfortable located in the pages of the waning

Plop! In a year rife with bilge, this is easily the worst thing we’ve read.

Jack: Was that supposed to be a surprise ending? I wasn't surprised. Had I not read the credits, I would not have known this was drawn by Ernie Chua, since it doesn't look much like his usually fluid work. One thing I am not surprised by, though, is another wasted effort by George Kashdan.

|

| Nick Cardy |

Ghosts 32

"The Hellfire Club"

Story Uncredited

Art by ER Cruz

"The Fruit of the Hanging Tree"

Story Uncredited

Art by Luis Dominguez

"The Phantom Laughed Last"

Story by Leo Dorfman

Art by Fred Carrillo

Jack: Peter Hain, a reckless and daring student at Cambridge in 1955, demands to be shown the inside of the room where "The Hellfire Club" held its final meeting 50 years before and then disappeared. After the caretaker gives Peter a history lesson, he opens the door. Peter goes in, sees something horrible, and disappears. Yep, that's it! Not exactly a plot, and Cruz's art doesn't help. For the life of me, I can't tell what happened to Peter.

Peter: I'm with you on the confusing aspects of the story but I thought Cruz's art was decent. I liked how he messed around with the layouts and avoided the same old 6-panels per page

Ghosts story art. That doesn't mean it gets a thumbs-up from me but it's nice to see something different in this title now and then.

|

| What is happening here??? |

Jack: In a small town in Bengal, India, ghostly figures appear each year as "The Fruit of the Hanging Tree," reminding villagers of a brutal crackdown by British soldiers a century before. When an engineer digs up the tree to build a new road, the ghosts of the dead emerge from the pit and go on a rampage until the tree is replanted. This is one of those stories by an uncredited artist where I feel like I recognize the style but I just can't put my finger on it. It's not good, that's for sure.

Peter: Nope, this is not good at all. Well, I'll give it half a star for the eerie panels of the ghosts hanging from the trees. That's pretty cool.

|

| 'Cause this is thriller, thriller night--- |

Jack: Paris, 1830, and Alfred does not believe in ghosts until a specter comes out of his mirror to frighten him. Alfred becomes a famous writer, but the specter torments him for years and really cramps his style with the ladies. Finally, he discovers that "The Phantom Laughed Last," the ghost is himself and he drops dead of "premature old age." It's a trifecta! Three awful stories make up this issue of

Ghosts, the comic we love to hate! You know what makes no sense? DC was about to put out a giant-sized edition of

Ghosts! I can't wait to see what

that entails.

Peter: By the 32nd issue, both Jack and I stand and applaud when a

mediocre Ghosts story is presented since we're so used to this bottom-of-the-barrel junk. Pretty sad. What's sadder is that the fabulous DC mystery artists like Dominguez, Carrillo, and Cruz have to illustrate these crappy Dorfman scripts (I'm assuming the other two are by Dorfman but the other two

Ghosts standbys, Boltinoff and Wessler, are equally as bad).

|

| Can you run that by us again? |

|

In Our Next TNT-Package!

On Sale June 1st! |