Pity poor Nora Manson! Day by day she sits at the window of her home in Larchville, a suburb of New York City, unable to move or speak but able to see and hear all that goes on around her. Her first husband was the scion of a wealthy family that owned and ran a bank in the city. When he died, she married Ralph Manson, who had worked his way up to a position of importance in the bank. Tragedy struck when her 18-year-old son Robbie, who had been working at the bank, was accused of stealing over $200,000. When the crime was discovered, Robbie could not be found, until Nora discovered him dead, hanging from the rafters in his attic room.

Not long after that, Nora heard movement in the attic and found that a man she knew well was spending time up there with the large sum of cash he had stolen from the bank. He had framed Robbie and murdered him, staging the killing to look like a suicide. To prevent Nora from revealing his crimes, he pushed her down the stairs, leaving her paralyzed and in shock.

|

| Phyllis Thaxter as Nora |

Nora survives Saturday night and, on Sunday, those around her have reason to suspect that there had been an intruder the night before. By Sunday night, Nora has recovered enough movement in one hand to provide clues to her nurse, who ventures into the attic and begins to piece together the truth. Just in time, it turns out, because the killer is back and his attempt to murder Nora is foiled by timely intervention by a neighbor.

|

| April 1947 |

- Nora Manson, the invalid who struggles to remember what happened to her and to her son as she also struggles to recover enough movement to tell someone before she is killed;

- Milly Sills, the young night nurse who is devoted to caring for Nora and who acts as her replacement, going up to the attic to uncover the truth;

- Emma, the devoted housekeeper;

- Hattie, the cook.

- George Perry, the young man next door who loves Millie and saves the day;

- Bruce Cory, brother of Nora's deceased husband and one of the two main suspects as the book nears its end;

- Ralph Manson, whose devoted attention to his invalid wife hides a terrible secret.

Lawrence creates an effective mood of suspense and dread throughout the novel, using multiple perspectives and flashbacks to slowly provide the details of what happened in the past and how it affects what is happening in the present. At the start of the novel, the reason for Nora's paralysis is unknown; the scene where she is pushed down the stairs occurs late in the book. Robbie's suicide comes early in the novel's second half, so the entire first half leaves the reader in the dark about two key events while providing just enough detail to make it clear that something terrible has happened. The third and final mystery is the identity of the killer, and this is not revealed until the very end of the story, in a single sentence. Juggling three mysteries along with the story of Nora's deadly weekend is a demonstration of technical skill by the novel's author.

Born Hildegarde Kronmuller in Baltimore in 1906, Hilda Lawrence had a short but memorable career as a mystery writer, publishing four novels between 1944 and 1947 and then three two-part mystery novelettes in women's magazines between 1947 and 1951. Including a short story in 1948 and an amusing article setting out her thoughts on writing mystery novels in 1945, she seems to have written for publication only from 1944 to 1951. She died in 1976.

The attic in Composition for Four Hands is both a place and a symbol, representing Nora's mind. The attic is the location of the traumatic events that set the story in motion; it has a door that is firmly locked with a key that has been lost. Only at the end of the book is the key located and the attic opened, allowing Milly to discover physical evidence of the crime and allowing Nora to unlock her own memories of what really happened and who is responsible. Composition for Four Hands is not a great literary achievement, but novels such as this can sometimes be made into great films.

William Gordon and Charles Beaumont are credited with the teleplay for the TV adaptation, retitled "The Long Silence." How did they handle the narrative-driven, non-linear approach to storytelling found in the novel? Often, writers for the Hitchcock show would move flashbacks to the beginning, in order to present the story in clear, chronological order. Did they turn much of the narrative into dialogue? Did they add a scene with gunplay? And what of the creature that creeps at night on four yellow hands? In the book, these turn out to be painted furnace gloves, two of which are attached to a pair of shoes. Will this detail--which gives the novel its title--even make it into the film?

William Gordon and Charles Beaumont are credited with the teleplay for the TV adaptation, retitled "The Long Silence." How did they handle the narrative-driven, non-linear approach to storytelling found in the novel? Often, writers for the Hitchcock show would move flashbacks to the beginning, in order to present the story in clear, chronological order. Did they turn much of the narrative into dialogue? Did they add a scene with gunplay? And what of the creature that creeps at night on four yellow hands? In the book, these turn out to be painted furnace gloves, two of which are attached to a pair of shoes. Will this detail--which gives the novel its title--even make it into the film?

|

| Michael Rennie as Ralph |

Ralph is on his way out of the house with a suitcase that night when Robbie returns home and confronts him with the evidence of his crime; they argue, and when Robbie insists that Ralph come upstairs with him and confess to Nora, Ralph puts one hand over Robbie's mouth and the other on his throat. He is so forceful that he accidentally kills Robbie. About to get in his car to leave the house, Ralph sees a coil of rope hanging on the garage wall and gets the idea to stage a suicide. As he types the fake suicide note, the noise of the keys awakens Nora, who comes upstairs and discovers the grisly scene. As in the novel, Ralph pushes her down the stairs and she is left paralyzed and unable to remember what happened.

|

| Rees Vaughn as Robbie |

The TV adaptation also solves problems in the novel having to do with timing and motive. In the book, it is not clear why Nora is suddenly in danger or how long ago Robbie died and she was injured. In the film, she is hospitalized and a nurse is assigned to care for her--Milly Sills has been renamed Jean Dekker. Voice-over narration is used to allow Nora to express her thoughts, her confusion, and her inability to understand why she is in the hospital or what happened to her. Over time, she begins to recall that there is something wrong involving Ralph. After six weeks, she is moved home from the hospital and the doctor says that she appears to have a mental block brought on by trauma. Nurse Dekker accompanies her home from the hospital as her private nurse and, a week after she returns home, the sound of the nurse typing her treatment note brings back Nora's memory of what happened. The film has now joined up with the early part of the novel, almost halfway through its fifty-minute run time. The discovery of Robbie's body and Nora's fall down the stairs are replayed in a short flashback, with Nora's face super-imposed over the scene to show that her memories have come flooding back. Her fingers begin to twitch and it is clear that Ralph is in great danger of being identified as the man who killed her son and caused her paralysis.

|

| Natalie Trundy as Nurse Dekker |

The nurse discovers that Nora can communicate by moving her fingers, and this allows her to convey her fear of Ralph, who slips into the room again when Nora ventures downstairs to tell George what has happened. Ralph shakes Nora and she finally screams, bringing first Nurse Dekker and then George, who subdues Ralph with a few well-placed punches. As the screen fades to black, Nora recovers her ability to move and speak, and a tragedy has been averted.

|

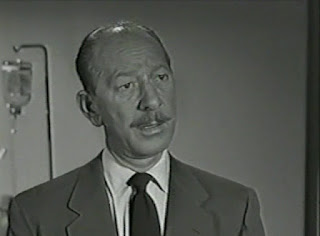

| Vaughn Taylor as Dr. Babcock |

"The Long Silence" is a superb hour of television; exciting and suspenseful, it benefits from strong direction, outstanding acting, and a good score by Lyn Murray. Director Robert Douglas makes fine use of shadows in several scenes, especially when Robbie is found hanging in the attic and we see only the shadow of his dangling corpse as it is reflected on the wall. Michael Rennie is utterly convincing as Ralph, portraying a man who never takes responsibility for his evil acts and always seeks to blame others for what he has done. Phyllis Thaxter also turns in a top-notch performance as Nora, conveying great emotion with just small movements of her face and through effective voice-over narration. Finally, there is no need for gunplay--the villain is subdued with fists, in a denouement that is consistent with the book.

|

| James McMullan as George |

Sharing the writing credit with Charles Beaumont is William Gordon (1918-1991), another Hollywood Renaissance Man. He started out writing for radio in the 1930s, then worked as an actor, writer, director, and announcer on radio and early television. He continued writing for and acting on TV into the 1980s. Gordon both acted in and wrote for Thriller, acted on The Twilight Zone, and directed six episodes of The Alfred Hitchcock Hour.

The score is by Lyn Murray (1909-1989), a prolific composer who started out in radio, then worked in film from the late 1940s through the late 1980s and on TV from the mid-fifties onward. He won an Emmy in 1986, scored Hitchcock's To Catch a Thief (1955), and wrote the music for 35 episodes of The Alfred Hitchcock Hour.

|

| Connie Gilchrist as Emma |

Phyllis Thaxter (1919-2012), who plays Nora, started out on stage, then began acting on screen in 1944. She contracted polio in 1952 and, while she recovered quickly, the experience may have given her some insight into her paralyzed character in "The Long Silence." She was on Thriller and The Twilight Zone, and she was on Alfred Hitchcock Presents six times and The Alfred Hitchcock Hour twice. At the end of her career, she played Ma Kent in Superman (1978).

The lovely Natalie Trundy (1940- ) plays Nurse Dekker; she was born Marguerite Campana and acted on screen from 1953 to 1978. One of her five husbands was producer Arthur Jacobs, who cast her in the second through fifth Planet of the Apes films. She was also on Thriller and The Twilight Zone. This was her only appearance on the Hitchcock series.

In smaller roles:

*Vaughn Taylor (1910-1983) as Dr. Babcock; a busy character actor from 1946 to 1976, he was in Screaming Mimi (1958), Psycho (1960), and countless TV shows, including The Twilight Zone and Thriller; this was his only appearance on the Hitchcock show.

|

| Claude Stroud as Ogden |

*Connie Gilchrist (1901-1985) as Emma; she was a busy character actress on screen from 1940 to 1969; she was in three episodes of the Hitchcock show, including "A Home Away from Home."

*Claude Stroud (1907-1985) as Edgar Ogden, who helps bring Nora out of the bank in the first scene; he was on screen from 1933 to 1971 and he appeared in three episodes of the Hitchcock show, including "The Last Escape."

*Rees Vaughn (1935-2010) as the unfortunate son, Robbie; he had a brief career, almost exclusively on TV, from 1962 to 1970; he was on the Hitchcock show three times, including "The Big Kick."

The two-part serialization of Composition for Four Hands in Good Housekeeping may be read for free online here and here. "The Long Silence" is not available on US DVD or online.

Sources:

The FictionMags Index. Web.

Galactic Central. Web.

IMDb. Web.

Lawrence, Hilda. "Composition for Four Hands." Good Housekeeping April 1947. Web.

Lawrence, Hilda. "Composition for Four Hands." Good Housekeeping May 1947. Web.

Lawrence, Hilda. Composition for Four Hands. NightHawk, 2016. E-book. In Duet of Death, first published in 1949.

Lawrence, Hilda. "Domesticating the Murderer." The Saturday Review of Literature 17 Feb. 1945: 16-18. Unz.org. Web.

"The Long Silence." The Alfred Hitchcock Hour. 22 Mar. 1963. Television.

"Robert Douglas, 89, Suave Actor Turned Director." The New York Times 16 Jan. 1999. Web.

Wikipedia. Web.

"William D. Gordon." Web.Charles Beaumont on Alfred Hitchcock Presents/The Alfred Hitchcock Hour: An Overview and Episode Guide

Charles Beaumont's contributions to the Hitchcock TV series, like those of his friend Richard Matheson, were not extensive. Beaumont adapted "Backward, Turn Backward" for Alfred Hitchcock Presents in 1960 and, while the adaptation was faithful to the story, the episode is not memorable. He then co-adapted Hilda Lawrence's novel, Composition for Four Hands, for The Alfred Hitchcock Hour in 1962, and the show is exciting and suspenseful.

EPISODE GUIDE-CHARLES BEAUMONT ON ALFRED HITCHCOCK PRESENTS/THE ALFRED HITCHCOCK HOUR

Episode title-“Backward, Turn Backward” [5.18]

Broadcast date-31 Jan. 1960

Teleplay by-Charles Beaumont

Based on-"Backward, Turn Backward" by Dorothy Salisbury Davis

First print appearance-Ellery Queen's Mystery Magazine June 1954

Watch episode-here

Available on DVD?-here

Episode title-“The Long Silence” [8.25]

Broadcast date-22 March 1963

Teleplay by-William Gordon and Charles Beaumont

Based on-Composition for Four Hands by Hilda Lawrence

First print appearance-Good Housekeeping April and May 1947

Watch episode-unavailable

Available on DVD?-unavailable

In two weeks: Our series on the work of the husband and wife team of Francis and Marian Cockrell begins with "Revenge," starring Ralph Meeker and Vera Miles!

6 comments:

I'm not sure how many episodes she was in altogether, but when it comes to the two TV series, it's easy to think of Phyllis Thaxter as practically "the" Alfred Hitchcock actress.

Every time I read about another interesting episode NOT on DVD in the US, I give serious thought to picking up the UK sets to get the ones I need (amazing it's only £65 for all seven seasons of AHP, and while the set of AHH 1-3 is also £65, the three individual seasons are available for only £14 each!).

Grant, Thaxter was on eight episodes in total, which puts her near the top, but Pat Hitchcock has her beat with ten!

John, another option is ioffer, which is where I got mine. I just checked and you can get the whole hour series for about $20. The quality varies but at least you'll have it on US DVDs!

John-

I took the plunge a couple Christmases ago and bought the UK sets of what I didn't have (AHP 6 and 7 and the full box of AHHour) pretty cheap (I think Amazon was having one of their annual blow-out sales). If you've got a region free DVD player (and most people do these days), I'd recommend the UK sets. The quality is fantastic.

Another Great Review Of A Great Episode!

Thank you!

Post a Comment